History’s largest oil glut months away from topping world storage while tanker freight rates explode

Mar 20, 2020The largest oil supply surplus the world has ever seen in a single quarter is about to hit the global market from April, creating an imbalance of around 10 million barrels per day (bpd). An exclusive Rystad Energy analysis shows global storage infrastructure is in trouble and will be unable to take more crude and products in just a few months.

Our current liquid balances show supply surpassing oil demand by an average of nearly 6 million bpd in 2020, resulting in an accumulated implied storage build of 2.0 billion barrels this year.

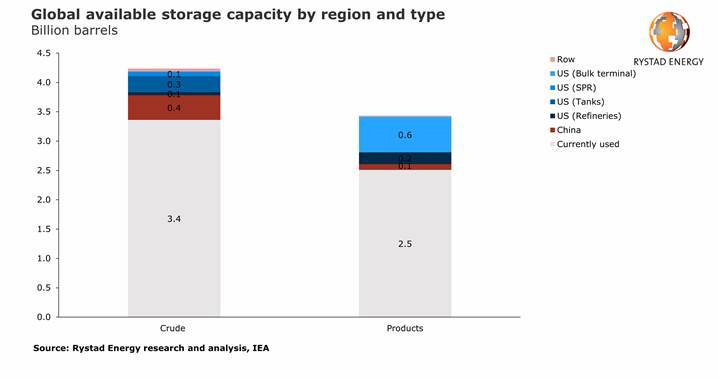

Based on our rigorous analysis, we find that the world currently has around 7.2 billion barrels crude and products in storage, including 1.3 billion to 1.4 billion barrels currently onboard oil tankers at sea. We estimate that, on average, 76% of the world’s oil storage capacity is already full.

There is essentially no idle storage capacity available on tankers, as Saudi Arabia and other producers might have already wiped out the available population of Very Large Crude Carriers (VLCC) for March and April 2020.

Our data shows that the theoretical available storage capacity at present is just 1.7 billion barrels onshore for crude and products combined. Using our estimate of an average of 6.0 million bpd of implied oil stock builds for 2020, in theory, it would take nine months to fill all onshore tanks. However, in practice we will hit the ceiling within a few months due to operational constraints.

“The current average filling rates indicated by our balances are unsustainable. At the current storage filling rate, prices are destined to follow the same fate as they did in 1998, when Brent fell to an all-time low of less than $10 per barrel,” says Paola Rodriguez-Masiu, Rystad Energy’s Senior Oil Markets analyst.

Floating storage normally uses VLCCs, which can carry about 2.0 million barrels. We estimate that there are about 802 VLCCs active globally with a combined capacity of 250 million deadweight tonnage (dwt), capable of collectively storing 1.8 billion barrels. The entire global fleet, including smaller Suezmax and Aframax vessels, is estimated to have a combined capacity of 630 million dwt or 4.6 billion barrels.

However, to keep oil flowing between regions, a ballast of around 50% is necessary as cargos often need to travel with no cargo to the destinations where they pick up oil, meaning that at any given time around half of the world’s fleet is booked traveling to consumer destinations, while the other half is empty on their way to pick up oil. This reduces the number of available vessels to about 57.

In addition, the workable available capacity is significantly lower as many of these vessels are under long-term charter deals or locked in ownership agreements, such as COSCO vessels with PetroChina. Waiting time at ports and repairs further shrinks the workable available capacity.

Due to the above-mentioned factors, using supertankers to float oil offshore might not be a viable option this time, as the planned OPEC+ output hike has not only limited the workable available vessels but also caused a surge in tanker freight rates. The cost of renting a VLCC on the spot market has risen from about $20,000 per day last month to between $200,000 and $300,000, depending on destination.

“We find that liquid supply will have to be reduced by around 3.0 million to 4.0 million bpd compared to the current production planning to bring the implied stocks builds closer to 2.0 million to 3.0 million bpd for 2020, which is the level of implied stocks build that we find sustainable in the short to medium term,“ Rodriguez-Masiu concludes.

Similar Stories

Change of Ørsted Region Americas CEO

View ArticleElkem reaches major milestone in advancing the circular economy for silicones

View Article

Strategic Marine delivers first purpose new build IMO Tier III CTV For Poland’s Offshore Wind Sector

View Article

U.S. Department of Energy: $20.2 million in projects to advance development of mixed algae for biofuels and bioproducts

View Article

New funding propels Pier Wind at Port of Long Beach

View Article

Most U.S. petroleum coke is exported

View ArticleGet the most up-to-date trending news!

SubscribeIndustry updates and weekly newsletter direct to your inbox!