Airships offer intriguing potential for project freight

Airships may be making a comeback and lifting project freight could be the reason.

Imagine airships longer than a football field gracing the skies, as they transport passengers and cargo almost silently and seemingly effortlessly. For countless many, it’s a dream that has held promise, romance — and heartbreak — for decades, a transformation in transportation that is always just beyond the horizon but has never quite arrived.

Are we finally there yet? Well, not quite, and it will likely be close to the end of this decade before any airship manufacturer can launch a truly commercial fleet. The field remains full of serious contenders, as well as those whose lofty promises appear to far exceed on-the-ground accomplishments. However, airships now have their best shot in almost a century. What’s more, not just luxury tourism, but specialized freight is a favored trajectory.

The Intriguing Potential of Airships

“An airship can carry very large loads, very long distances, and with zero emissions,” said Barry Prentice, Director of the University of Manitoba’s Transport Institute and a professor of supply chain management. “All the components to produce modern, reliable, high-quality airships exist. That’s not hype.”

The most significant impediment, Prentice and others believe, isn’t necessarily technology, but money. “The feasibility of producing airships is not the issue. It’s financing,” Prentice said. “The biggest problem for the airship industry is that you need a lot of capital to do this, because there’s no way to start small.”

Airships come in many varieties and forms, although it helps to divide them in two — non-rigid and rigid. Non-rigid airships, think blimps are good to about 15 tons lift, maintaining their shape through pressurized gas. These days, that’s helium, although the industry believes that hydrogen will be used in the future for all airships. Bigger airships require a frame or rigid skeleton to hold shape and carry loads.

These days, most commercial airship developers are focused on what’s called a hybrid airship. It’s an innovative design, “like welding two cigar blimps side by side,” described Prentice. Hybrid airships are generally about 20% heavier-than-air; engine thrust provides necessary lift. Their advantage, said Prentice, is the ability to drop off a load and return empty. A British airship maker, Airlander, is now developing all-electric engines for its hybrid airship, which would make this form of transportation completely renewable.

Climate change and the fast-growing concern about making transport more environmentally sustainable is one big reason why airships may finally get their place in the sun. But there are others, as well. The technology is already well developed. Airships can deliver a practical way to transport cargo to remote locations, whether it be disaster relief, wind turbine blades or resource extraction equipment. They can bridge the gap between costly and environmentally wasteful air freight transport and much slower surface or ocean transport. And they can work especially well, added Prentice, in island nations such as Indonesia and the Philippines, where normal logistics patterns just can’t handle the geography.

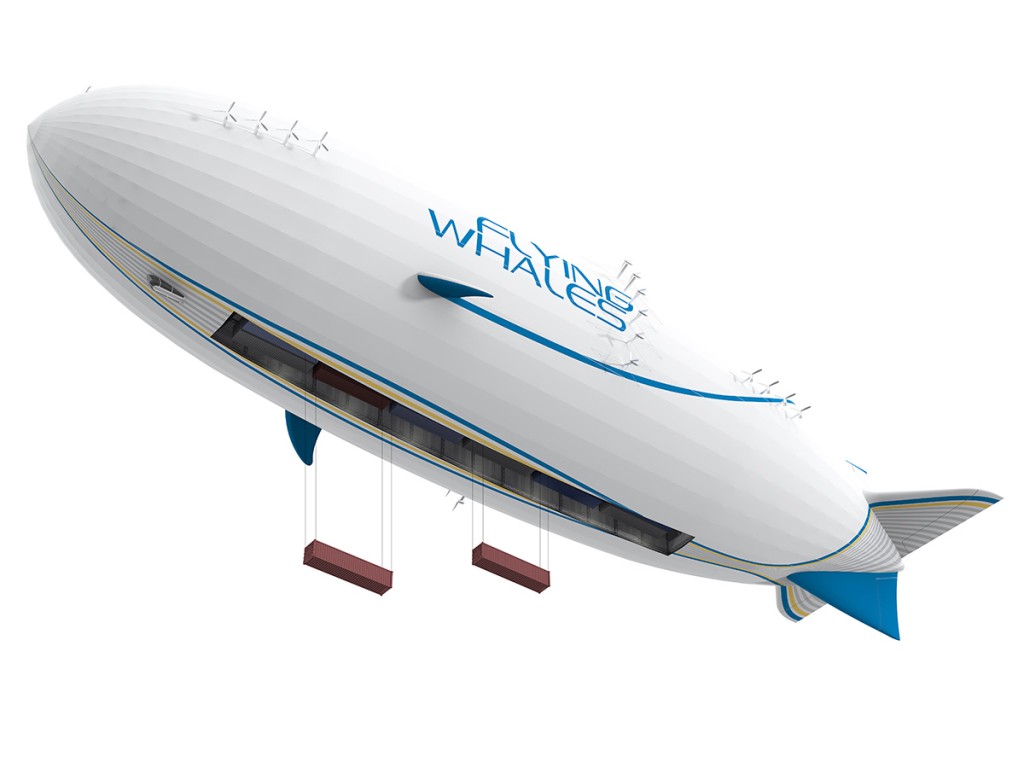

The Flying Whale Hybrid Airship

For more than a century, airships have sparked the imagination of countless inventors, engineers, and just plain dreamers. Today is no different.

The field seems to be ever changing. In 2016, a NASA Ames Research Center Study surveyed more than 50 entities with stated interest in developing airships. The study discounted almost 30 of these because of funding and staffing issues, but identified 18 as actively “designing, building or operating airships or aerostats.” Many of these names no longer exist or have been inactive for years. The most high-profile player in that list, Lockheed Martin, which benefited from millions of dollars of US Defense Department aid to develop an airship, and which had touted its product in 2016, announced this past May that it was shedding its work and its intellectual property and other assets were “transitioned” to a startup called AT Squared. The defense-oriented company appears to have lost interest.

These days, upwards of a dozen startups are attempting to develop airships in North America, Europe, and Asia. However, two are especially worth noting, not necessarily because of technological acumen or design superiority, but because of finance. They are Flying Whales and LTA Research & Exploration.

Based in Suresnes, France, Flying Whales is being backed in part by the French government, the Quebec government and is actively courting an unnamed government in Asia-Pacific.

“To bring these airships back into our skies, we need to make sure that we have the support of the state,” said Roman Schalck, Flying Whales’ head of communication. “This is a key for the success of the project.”

According to Schalck, the initial phase of Flying Whales producing hybrid airships will cost around 500 million Euros, of which half is expected to come from public financing. Flying Whales has already raised 162 million Euros from both public and private investors, including the governments of France and Quebec. “It is the very first time in 85 years any government has put money into a civilian airship,” Prentice pointed out.

The company anticipates the first test flight will take place in late 2025 or early 2026, with commercial operations targeted to begin in 2027. Flying Whales will have two final assembly lines, the first one in Bordeaux scheduled to open next year, the other in Quebec in 2026. A third is possible in Asia.

The company plans to produce 150 airships during the first decade.

Initially designed with remote logging in mind, the first generation Flying Whales airship will have a 60-tons payload capacity. The 200-meters-long airship will also boast of a 96-meters long, eight-meters wide, seven-meters tall cargo bay, which should accommodate extremely large project cargo as well as containers or general cargo. A sling will allow the carrying of oversized cargo, say, a tower, as well as being able to raise and lower payloads without landing. It will hover, with water being used as ballast.

The company envisions a range of 400 to 500 kms, returning to a base each day. This contrasts with Airlander, whose passenger-centric airship is being designed to travel up to 4,000 nautical miles, but with limited cargo capabilities.

“We want to have big airships back in the skies for cargo, not passengers,” said Schalck.

Flying Whales will produce a semi-rigid airship. The main frame will be composite. Inside the frame will be 14 gas cells holding helium. A textile envelope will surround the frame.

LTA Venture

While Flying Whales envisions a public-private partnership, LTA Research is being bankrolled by one of the world’s richest individuals, Sergey Brin, a co-founder of Google. He’s been mum about the effort, but according to a recent article in Bloomberg Business Week, LTA (for “lighter than air”) insiders say Brin has sunk more than $250 million in the effort through a family office.

A prototype, the Pathfinder 1, is now being assembled in an old NASA hanger in Mountain View, CA, in the Silicon Valley. Last year, LTA announced that it would move production to an even bigger hanger in Akron, Ohio, where the almost century-old hanger once housed Goodyear Aircraft’s production.

LTA’s initial airship will have about 28 tons of lift, according to LTA CEO Alan Weston, interviewed in that May article and in an accompanying video, which showed construction well under way. It is 122 meters long and can cruise at 60 knots for more than 2,000 nautical miles. Weston said the company wants to scale up to an airship that can carry more than 200 tons of cargo, with an emphasis on disaster relief.

The whole protracted saga to produce modern-day airships smacks of arrested development.

It may be difficult to picture now, but airship travel was fairly commonplace after World War I. In the 1920s and 1930s, transatlantic crossings took place regularly. Airships, not airplanes ruled the skies. That ended suddenly and tragically. In 1937, the Hindenburg zeppelin exploded in the skies over New Jersey, killing 37, with images of the deadly fireball searing public memory.

The Hindenburg disaster spelt the fiery end to airship travel for decades, but not necessarily its development. During the Cold War, for example, the US Navy used high-altitude balloons for submarine reconnaissance. After the September 11 attack, the US Department of Defense bankrolled airship technology for surveillance. And, of course, blimps continued to hover above sporting events.

As the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan wound down and threats of terrorist attacks receded, US government money began to dry up and thoughts of commercial ventures again began to bubble up.

LTA should begin testing the Pathfinder 1 this year. “It’s ready to come out the door and fly anytime soon,” said Prentice. “When that happens, people will actually see that we can build big airships and they can fly. I’m hoping we get airship mania,” he said.

Similar Stories

Boeing’s $3.9B Q4 losses highlight struggles with cost overruns and strike impact

Boeing reported $26.3 billion of cash and investments at the end of 2024, which incorporated a $14.1 billion cash use for the year and $24.3 billion issuance of equity and…

View ArticleSTV to spearhead design for VPRA’s Long Bridge South Package, linking Virginia and Washington, D.C.

STV, a leading professional services firm that plans, designs and manages infrastructure projects across North America, today announced the Virginia Passenger Rail Authority (VPRA) has selected the firm to lead…

View Article

Port Authority of New York and New Jersey’s commercial airports record busiest year ever for second consecutive year

View ArticleVAI welcomes Duffy as Secretary of Transportation

Association looks forward to collaborating on aviation innovation and safety

View Article

Ethiopian Airlines celebrates Chinese New Year 2025 with festive events

View Article

Chapman Freeborn celebrate twenty years in China

View ArticleGet the most up-to-date trending news!

SubscribeIndustry updates and weekly newsletter direct to your inbox!